Integral Equine Collective

"Grass affected" - real or pseudo science?

Over the last 10-20 years or so, the concept of “grass affected” horses has taken hold. This label covers an enormous range of symptoms (excitable behaviour, neurological issues, itch, colic, aggression, musculoskeletal issues… pretty much anything aside from traumatic injury or infectious disease!), all apparently caused by grass.

The big picture explanation of this is that horses did not evolve to eat grass like they do now, because they evolved in semi-arid grasslands and steppes. We typically think of the Przewalski’s horses in Mongolia living in places that look like this…

But the Mongolian grasslands can also look like this…

And sometimes in between like this…

It’s not always dry, mature, stalky grasses.

This presumption also discounts the fact that horses migrated and did extremely well all over Europe in a very wide range of climates that ranged from sub arctic, through temperate, semi arid and even sub tropical over the 100,000s of years that they were hanging about. This very complicated paper suggests that at the dawn of domestication horses in Europe were much more environmentally adaptable than has been previously believed based on Asian horse fossil data.

My point is, that while horses are very well designed to survive on coarse, very fibrous grasses – they are equally designed to cope with the new young growth that occurs in every environment at certain times of year, and apparently able to cope with temperature/warm and moister environments also, which would support more nutritious grasses for a longer growing season across the year.

Of course, wild horses in some areas had to cover much larger distances every day to get feed and water, faced predators, harsh winters without cosy shelters and generally had more difficult lives than our domestic horses. We have also bred extremely productive modern grasses in the last century which contain more nutrition than wild grasses ever had. This combination can spell disaster in certain situations – particularly in those breeds that are closer to their primitive types. Insulin resistance was beneficial to these horses to make the most of the good times, but is another topic altogether!

But the majority of horses that tend to be labelled “grass affected” seem to be (in my experience) the more “modern”, lighter breed horses that are further away from the primitive horse – thoroughbreds, warmbloods, quarter horses. The sorts of horses that originated in the less harsh parts of the world, that would have been less exposed to harsh conditions and had access to better feed more often – so (and I’m just theorising here) should be more tolerant of modern grasses.

So, the evolutionary background of this theory is, in my opinion, a bit shaky.

When I first started hearing about “grass affected” horses (when I was 19 and had a headshaker), it was all about high potassium levels in the grass (and lucerne hay).

Potassium is an extremely important mineral and electrolyte in the body - it's involved in the maintenance of acid-base balance, osmotic pressure (fluid control) and a crucial ion involved in neuromuscular excitability (electrolyte = conducts electricity when dissolved in water).

Luckily for horses, potassium is ABUNDANT in their natural diets, and according to the NRC Nutrient Requirements of Horses, it is "normal" for potassium intake to greatly exceed the estimated minimum requirements.

I strongly agree with this - any forage based diet I've every analysed has anywhere between 5-10 times more than the text book potassium requirement of between 25-50g. This is because all forages typically contain at least 1-2% potassium - if a horse consumes an average of 10kg of this forage over a day, its daily intake will be a MINIMUM of 100g. Most grass and hay analyses I see actually have between 2-3% potassium, which ups the daily intake to 300g, just for the base forage portion of the diet!

Again, luckily for horses, they are very efficient at excreting potassium through the kidneys - and the more that is consumed, the more the rate of excretion is increased through urine, faeces and sweat. This is a totally normal process. Sweat is a huge factor in potassium loss, and potassium deficiency can be a problem in heavily exercising horses, especially in hot humid climates - as horses do not have very good mechanisms to conserve potassium.

So the horse's system is very prepared for the "excess" of potassium it naturally encounters day to day. The NRC suggest that the maximum amounts listed are in fact nowhere near levels that could cause toxicity, and potassium excess has not been reported in the scientific literature to date.

There is a genetic syndrome - hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (HYPP), which causes horses to be very sensitive to potassium, and it is recommended to keep their diets under 1% potassium (100g - note this is still 2-4 times higher than the minimum requirements).

Interestingly, veterinary experts in treating HYPP do not recommend restricting grazing fresh pasture, as even though it can be high in potassium per kg DRY MATTER, the fact that pasture is usually 80% water means that the rate of consumption is much slower than a dry feed/hay, and thus will not produce high blood potassium levels.

And finally - falsely high serum potassium levels are EXTREMELY common due to blood sample handling errors. I previously worked in a hospital pathology laboratory, and every day there would be samples that needed to be recollected or the potassium result discounted - this is due to haemolysis of the sample, which is where the red blood cells begin to break down and leak their contents into the serum. This can occur due to collection technique, if the sample is not correctly agitated post collection, or if it is left for too long before spinning to separate the red cells from the serum.

Horse blood is even more prone to this issue than human, as they have very high levels of potassium in the red blood cells - so even a very slight amount of haemolysis can result in an elevated potassium result.

So, back to “grass affected horses”. It is true that rapidly growing grasses have higher potassium levels than dormant ones, and that lucerne tends to be a little higher than grasses, but the difference means little in the context of ALL forage being high in potassium! This rather scientific theory of excess potassium causing all manner of behavioural and neurological problems simply doesn’t stand up in healthy horses.

Over the years, I have noticed that “grass affected” could also apparently be caused by high protein/nitrogen/nitrates. It’s explained that modern grasses have high levels of protein because this is beneficial to ruminant livestock, who can make better use of high protein levels and convert ammonia to protein via the rumen bacteria. Horses, on the other hand, cannot. But non-protein nitrogen contained in forage is rarely ammonia, but nitrates/nitrites (the biochemistry between these two is super complicated), which are produced under rapid growth that follows stress – not normally in healthy pastures.

Nitrates are plant compounds found in many types of plants which can convert to nitrites in the horse's digestive system. Nitrites can inhibit oxygen use in animals and can be toxic, as well as interfering with iodine.

Typically, horses are not considered very sensitive to nitrate/nitrite toxicity (compared to ruminants such as sheep and cattle), and acute toxicity is quite rare, however there are concerns that breeding stock and sensitive horses such as those with laminitis may be affected by lower concentrations of nitrates that are occasionally found in pasture and hay.

Nitrate can accumulate in pastures or hays that have had excessive nitrogen fertiliser application and young, lush growth (particularly after drought conditions) can also be quite high.

Nitrates can definitely be a problem at certain times and could be behind some odd symptoms – but they are not “normal” in grasses – this is like blaming all hay for causing respiratory issues because sometimes the bales are mouldy…

Potassium and protein are the main supposed villains of this story, but “grass affected” is also explained to be caused by high calcium/low magnesium in young grass, high sugars/starch, mycotoxins, phytoestrogens and more. All of these things can cause problems, but to blame all “lush” grass for them (and have a convenient supplement with mystery ingredients that fixes it…) is in my opinion pseudo-science. There is NO scientific evidence to support this theory as a whole.

Having had this long rant, you may be thinking “but my horse definitely shows symptoms in spring/on green grass and is better when I take them off”. I 100% believe you – and in most cases it can be explained by the horse being exposed to a sudden change in diet – suddenly higher sugars, mineral imbalances, gut microbiota trying to digest new things! Especially in a horse that may not have a balanced, diverse diet that supports mineral balance and enough gut microbial diversity to promote resilience to change. And of course, there can always be individuals that are, for want of a better word, "allergic" to various things, and there's no reason to think a horse could not be allergic to rye grass, or clover, or brome, or whatever species - but it's unlikely to be a widespread (and not clinicially reported) phenomenem.

These sudden changes will be more extreme when you have pastures that are stressed, single or few species, and grown on unhealthy soils (synthetic fertiliser etc), and if you have a horse that is struggling with other underlying health (especially gut) or stress issues. Taking the horse off pasture for good is one solution (although many hays can have the same “problems”), but providing diverse forages and ensuring minerals are correctly balanced may, in the long run, make the horse more resilient to the changes in pasture it will see year in, year out, and was designed to deal with.

Paddock walk December 2023

There's a couple of editing glitches in this one, but I'm sure you get the picture!

This is what our pastures are looking like at the moment - lots of mature growth from spring which I believe will be best for them from a sugar and fibre perspective, and from a soil building/root system point of view, which will be important to hold water and reduce plant stress.

I should really take some more grass samples for testing...

Feel free to ask any questions!

Grass analysis 2020-2023, seasonality, average rainfall... lots of graphs!

I thought I'd actually collate and try and to understand if there are any trends in the pasture testing data (on our propery at Duffys Forest) I've done over the last couple of years. I have a very strong suspicion that alot of the advice that is taught and given out (including by myself) about pasture nutrients (especially sugars) is not necessarily relevant to all situations - I think it's highly influenced by location, climate, weather patterns, species etc... which is why I always recommend doing some of your own pasture testing to get a feel for what happens in your situation.

Sadly, I did not undertake the sample collection in a particularly scientific way - collecting a sample on the first day of every month for example would have been nice! Instead I was generally testing for a specific reason... typically I might have been worried about weight gain, or laminitis, or just checking to see if the grasses had matured enough to give lower sugar levels. This means there is a bit of a bias towards testing at times when I thought sugars might be high, and a lot less testing done in winter or high summer when the grasses were super mature. There are also lots of gaps, and some months had multiple tests, which I averaged to try and simplify the graphs...

But still, I think it's an interesting collection of information... I hope someone else out there does too :P Please feel free to comment with questions (I've tried to make certain information really clear, but I know not everyone is familiar with looking at graphs!) or observations I might not have seen!

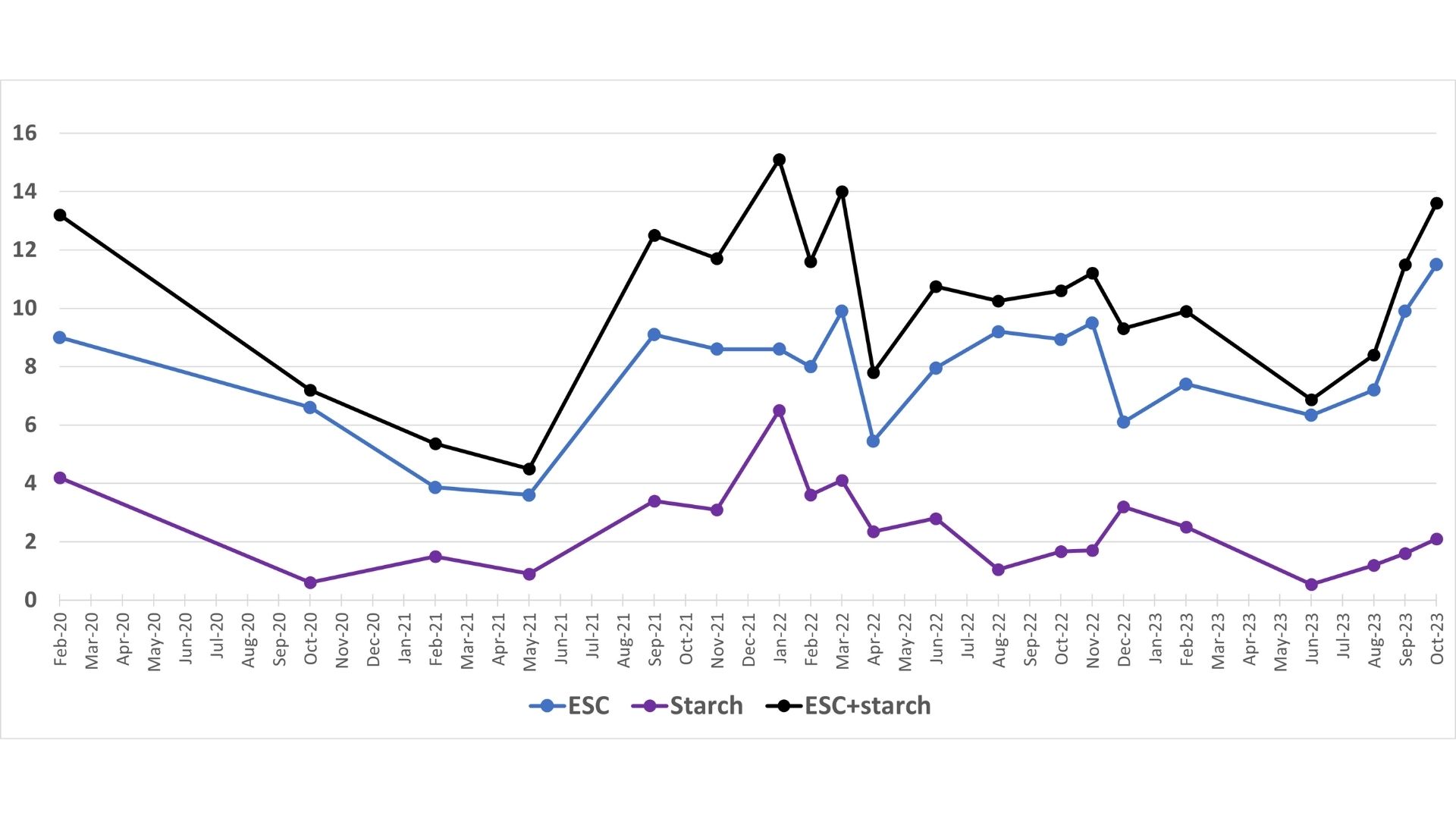

First things first, this is the ESC and starch percentages from Feb 2020 until October 2023, with no other information. You can see frequency of testing has increased as time goes on - there may well have been more variation in 2020 that I didn't catch in the two samples I took.

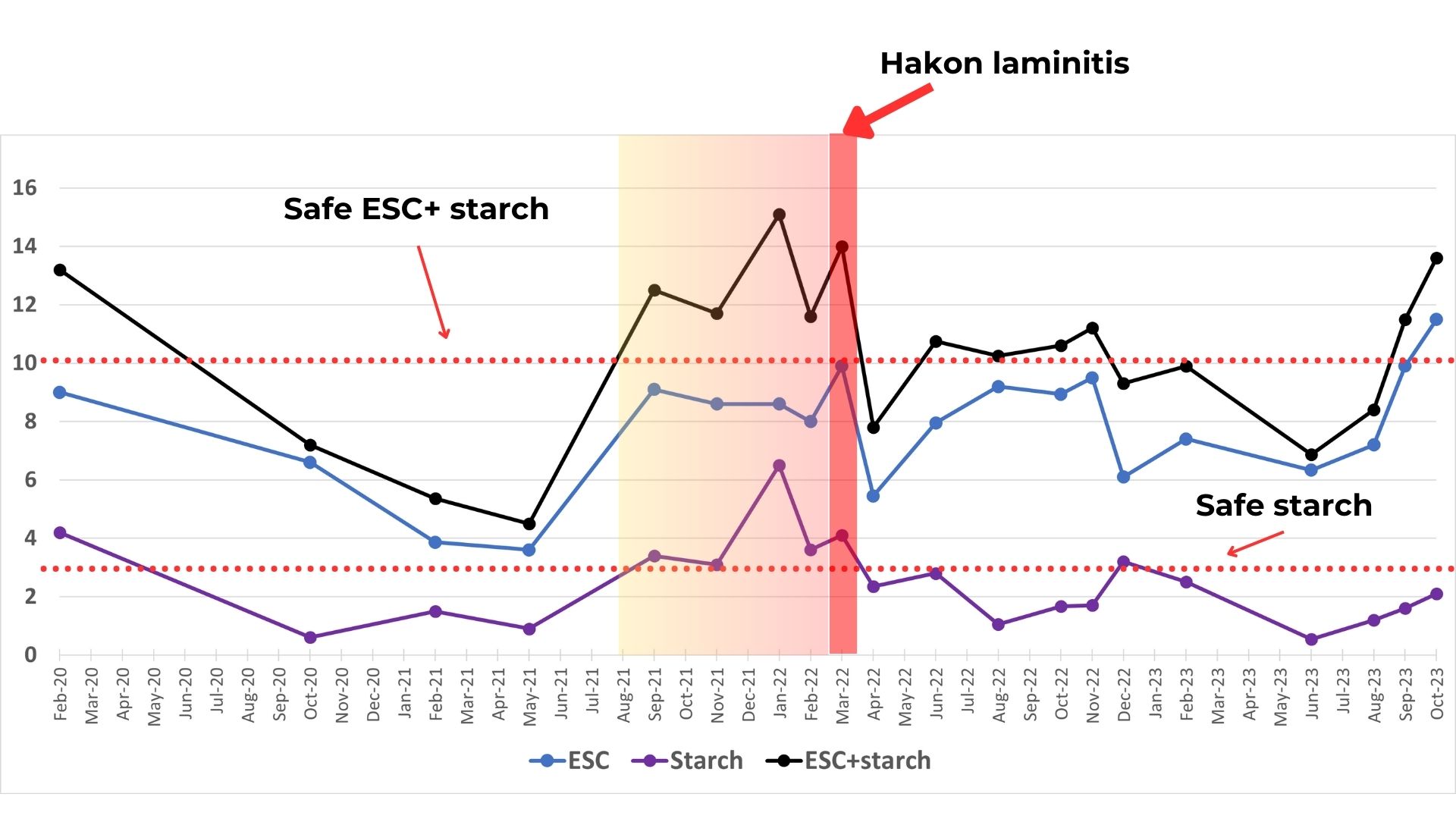

I'm now going to add some context to these lines... adding in the "safe" thresholds for laminitis/insulin resistance, and also the period where our Hakon had his laminitic episode. I highlighted the preceding 6 months as it was consistently above 10% ESC+starch - strikingly this was mostly because of the starch content being consistently above 3%, which is quite unusual.

I didn't mark it on the graph, but Hakon actually returned a normal insulin test in October 2021. This suggests to me that it took quite some time for his metabolism to start to struggle in this environment (he was also for various reasons not in very much work at this time), to the point where actually got laminitis - it was not a single day or even week of high sugars that triggered it. He also had no hoof rings until the laminitic episode in March - hoof rings are known to be predictors of laminitis (as they can indicate subclinical changes in the hoof).

So from here, I wanted to see if there was some sort of predictive pattern to sugars and starches - as you can see there have been periods of very low sugars and also moderate (even our highest ESC+starch at 15% is not crazy high in the scheme of highly productive species). The average result is just under 10%.

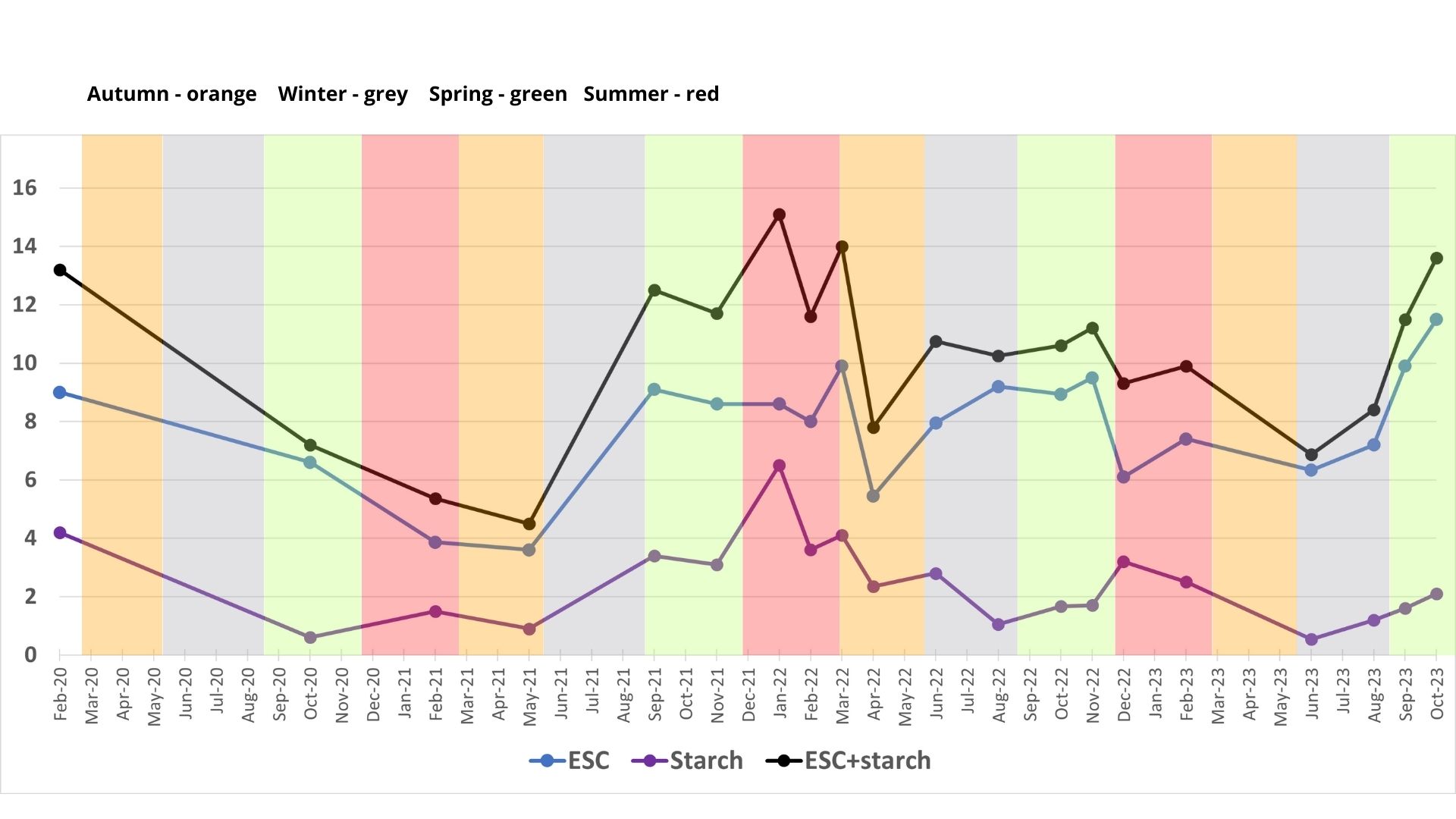

Firstly, lets look at seasonal patterns...

Focus on all of the green colour bands (spring) for example - the sugar/starch levels are all over the place with no clear seasonal pattern! Autumn seeeeeems to tend to have slightly lower results, but it's still pretty variable. This is quite contrary to a lot of northern hemisphere research - which makes perfect sense as in our climate, autumn sees the gradual end of full throttle summer growth of our warm season C4 grasses - long, mature, fibrous plants that the horses tend not to like! In cooler climates the warm season grasses die off earlier, allowing C3 species to get going in autumn, something we don't get. We also don't get frosts in autumn here.

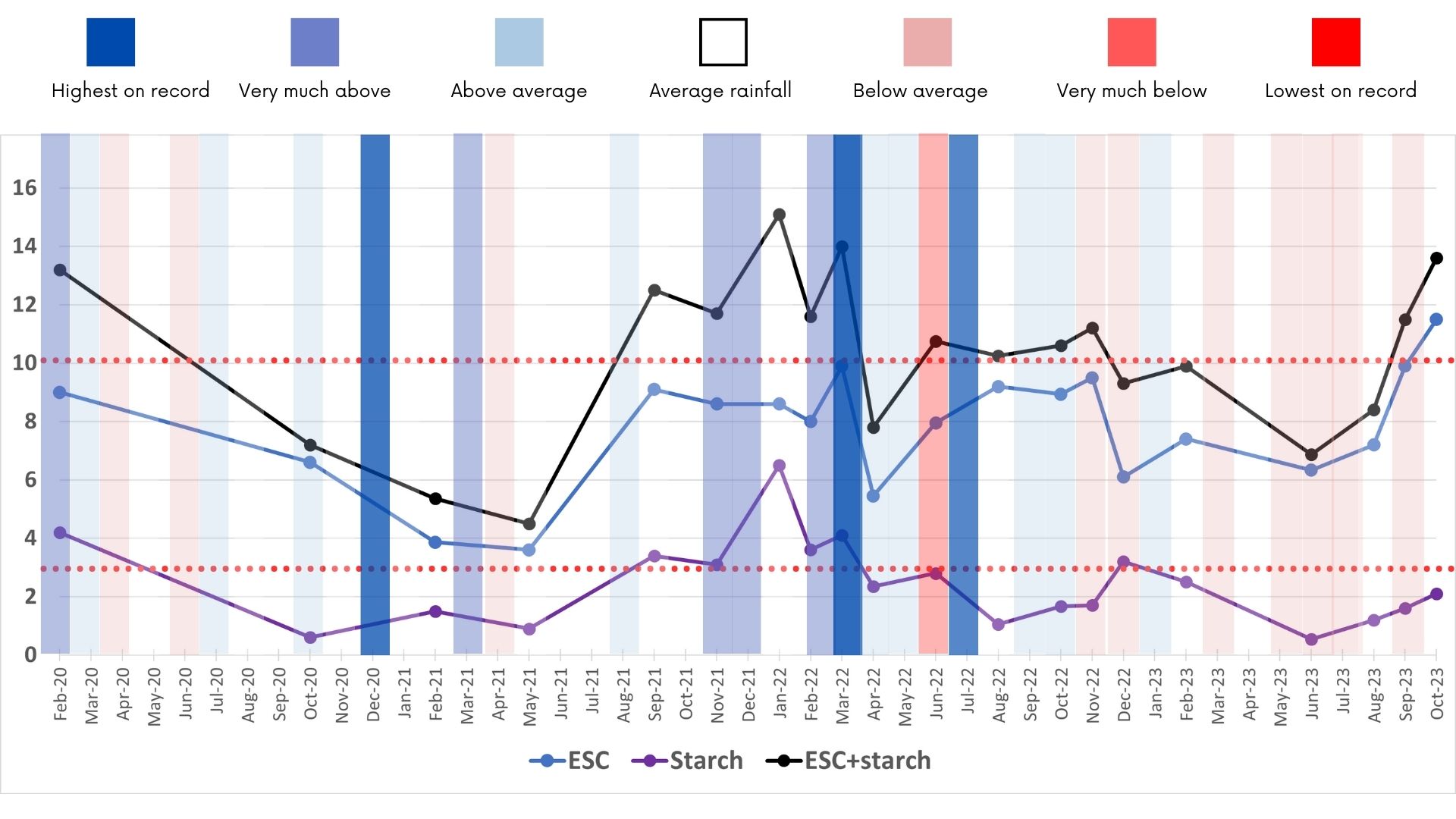

So seasons don't seem to explain the fluctations. What about rainfall? I think we all recall that the last couple of years were very wet, and I know the paddocks were extremely waterlogged (even though we have reasonable drainage being on a slight slope). I went to BOM and got the monthly rainfall ranges...

I was quite suprirsed to see average and below average months in 2021, but there you go! Having said that, you can see that there's a lot more blue in the lead up to our high sugar periods, and very little dry periods. Rain, on rain, on rain, may be a potential stressor in the grasses, leading to abnormal starch accumulation. Certainly I remember that the grass grew to a point in spring/summer 2021, but then seemed to just get "stuck" and sit there at about knee length (when normally it would continue to grow well past this height in the summer).

If we look at the lower sugar periods (April 2020- July 2021 and Aug 2022-Aug 2023) it looks to me like we have more variable rainfall each month, some months it rained more, some less, but the overall rainfall looks more average over those time periods - no long periods of wet OR dry. It will be interesting to see what happens over the next few months as we seem to be in an extended mildly dry period and sugars are currently going up (although we have had a lot of rye and C3 species in those last couple of samples, which may not be 100% representative). I'll have to extend the graph in a couple of months and see what role the species change has (when our kikuyu, paspalum and rhodes grass dominates) V the weather patterns.

It makes sense to me that anything above or below "normal" will challenge the plant and may lead to stress accumulation of sugars.

I could have gone on to look at temperatures etc... but I do have a life (lol) and had to stop somewhere. Can do by request though!

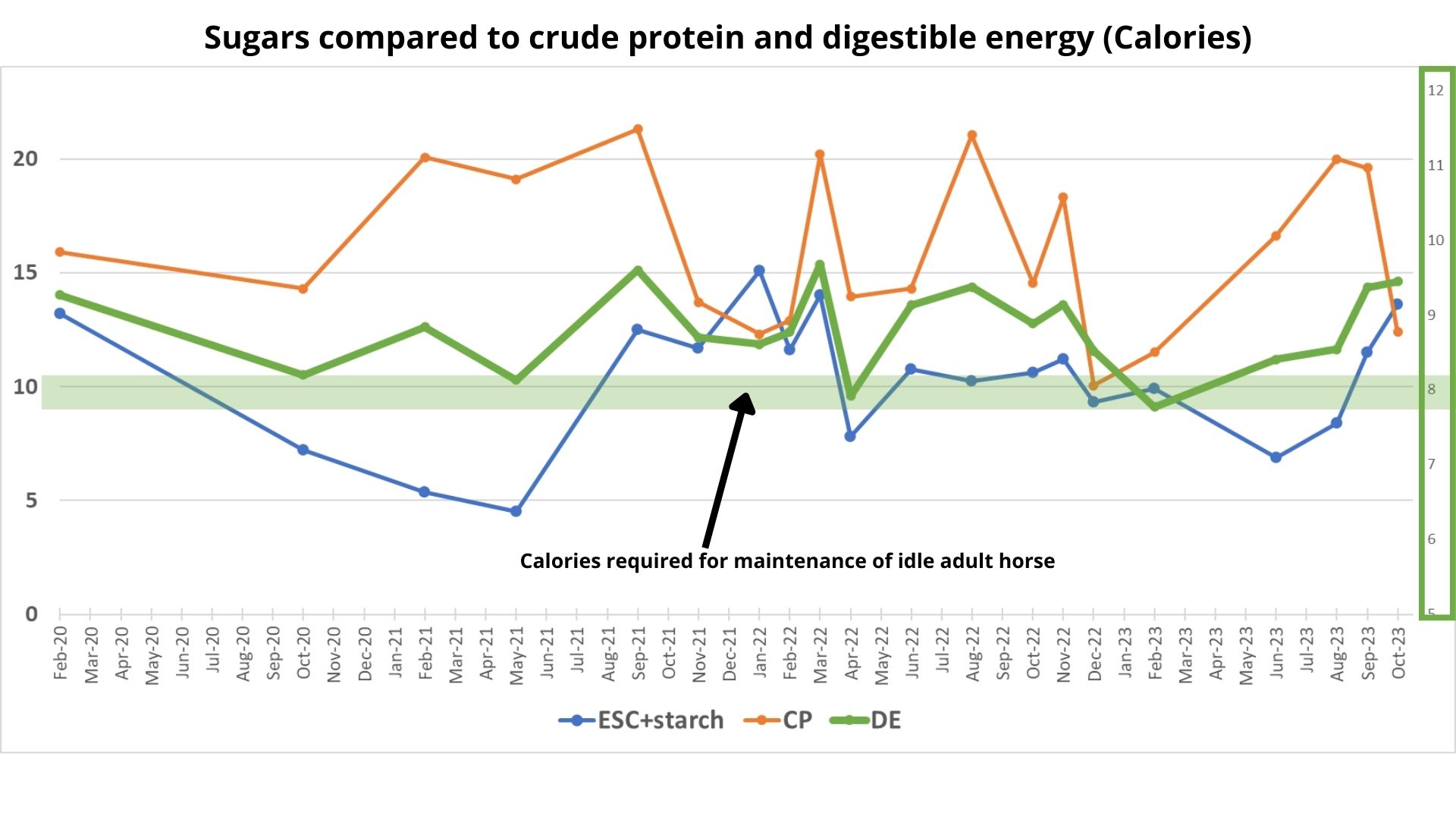

Finally I also plotted digestible energy (calories), crude protein and sugars on one graph to see how they vary compared to one another.

This graph might be a little more confusing as energy is measured in a different unit (megajoules), which is on the right hand axis, than protein and sugars (which are a percentage) on the left. The pale green horizontal bar shows the approximately level of calories needed to maintain weight on a horse at rest (just under 80MJ). So it's not too hard to see why our horses always tend to be a little on the chunky side! Having said that, I always sample the "best" of the paddock - not the whole plant, so as they graze down the area they will actually be accessing lower levels of nutrients over time.

I thought the most interesting part of this graph is how it shows that sugars and proteins are often (but not always...) inverseley related - that is that protein tends to be high when sugars are lower - and this is a well described phenomonem in grasses as protein tends to be high in fast growth plants, which are using up their sugars from growth rather than storing them for later.

Calories overall do not seem to be influenced strongle by either protein or sugars alone, but a combination, which makes sense as the horse extracts energy from many different nutrient fractions (and the biggest one being digestible and fermetable fibres, which now I think I should have plotted too! Again, happy to do so if anyone wants!).

Keen for comments and questions!

Instructional video: How to properly dry your grass sample

Once you collected your sample, it's important to get it dried ASAP - this is to preserve the nutrients as is in the sample. If you leave the sample to wilt and dry naturally, it will actually keep "respiring" as it slowly dies (morbid!), using up sugars in particular, which will give you a falsely low result.

Please be slow and CAREFUL when microwaving - it gets very hot and can go very quickly at the end. I don't want to hear about anyone setting their microwaves on fire!

Instructional video: How to take a grass sample

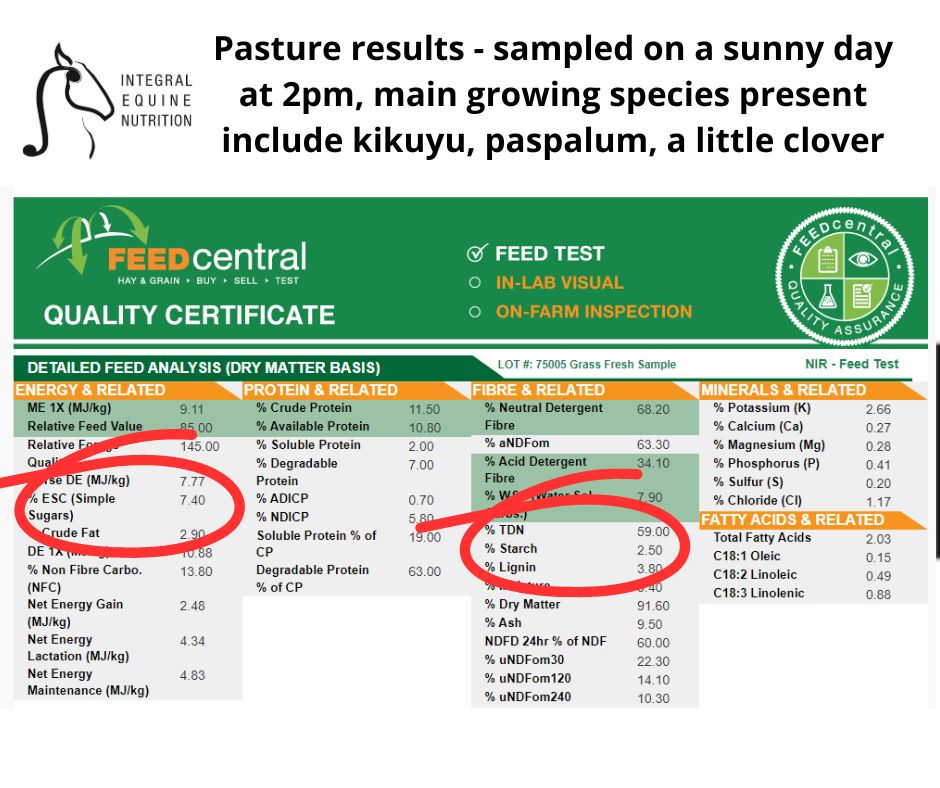

I LOVE getting results back from pasture tests. We make a lot of generalisations about "grass" when it comes to feeding horses - good grass, bad grass, morning is better, natives are better, spring grass is sugary etc etc. But these assumptions are made based on research that was almost invariably NOT done in your paddocks, and probably not even in our hemisphere...

Many people will say "oh but grass testing is a waste of time because the nutrients change all the time" - yes, particularly the sugars are known to vary over the day, but even with that in mind, wouldn't you rather know something than nothing? Once you start taking semi regular samples (noting the time of day, conditions etc - taking a photo is an easy way to track that), you will start to understand a bit more about how your own pasture ranges in nutrients, and can make better nutritional and land management decisions based on this.

So - here's a video explaining how to take a good grass sample, and I'll be follow that up with how to properly dry your sample before sending it to the lab. As always, please feel free to ask questions or discuss!

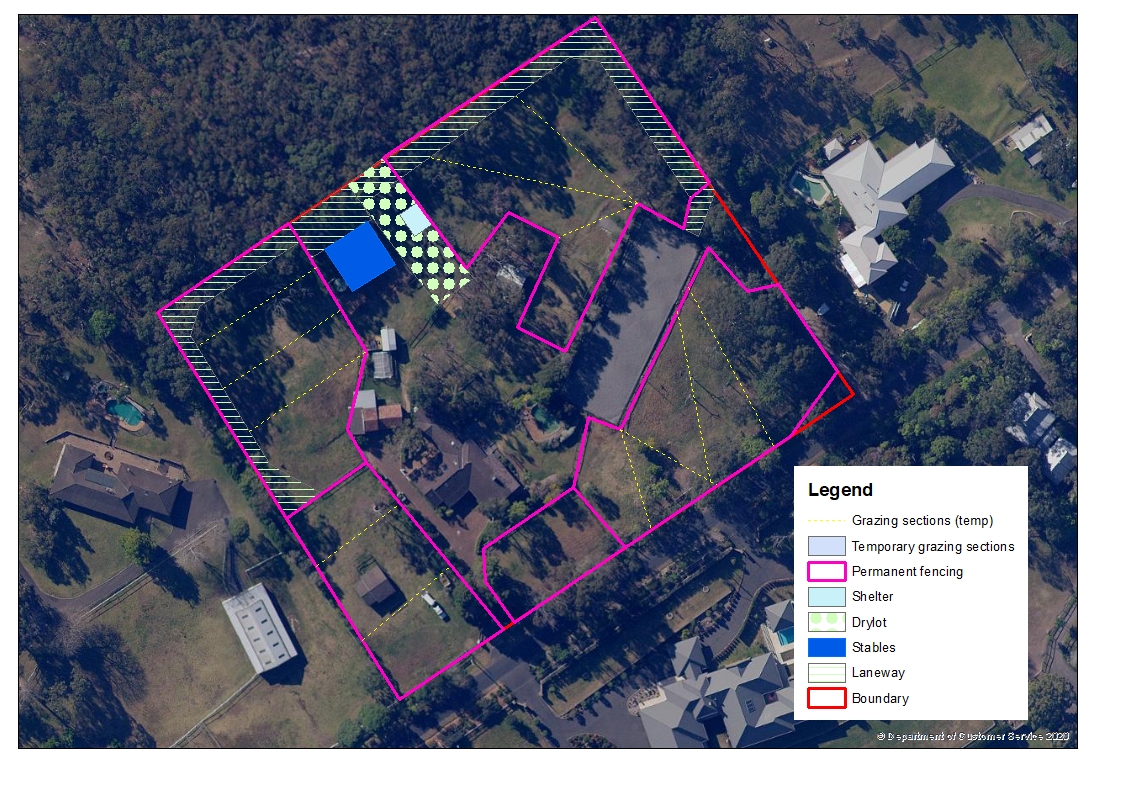

Our property lay out

Here's a quick map up of our property (5 acres, approximately 2.8 acres under paddock) - we're developing a semi permanent laneway that runs along the back and down the sides so that the horses can have access to any of the paddocks we choose without having to change too many fences and gates!

They always have access to the drylot (which I've drawn a little narrow here, oops!) and then go either right or left into the laneway that gives them access to whichever section we're currently grazing. They have roughly 4x4m stables with large yards at nighttime. If you check out the previous post you can see how the drylot shelter etc is set up.

The dotted yellow lines are roughly where we might put our temporary electric fencing for each grazing section - I've drawn them all in to show you how might divide up the paddocks, but there would only be one set up at a time. Video of me setting up a new section.

How long the horses graze in each section depends on how much grass there is, how quickly they're eating it etc, but we would typically graze each bit for 1-2 weeks (bearing in mind because of our laminitic they are only out for a half day in the mornings most of the time). We usually sacrifice a "winter paddock" (often the one I set up in the video as it gets more sun in the winter) and leave them their much longer to trash at the end of winter while waiting for the grass growth to get going early in spring.

When they are using the bottom left paddocks we use the arena as an extension of the laneway (there are gates at each end and on the sides) and the horses use it as a secondary snooze sport.

Top tip when thinking about how you might set up a grazing system, especially if you are using laneways is that many horses find it INCREDIBLY difficult to turn back on themselves to get somewhere (i.e. use a maze). So if the end of your grazing section is closer and in line of sight to the dry lot, it will take some convincing to get them to turn around, go through the gate to the laneway and back around. But, everyone gets more exercise :P

If you look at the mapy and compared it to the laneway walk and talk video, I hope you can get a good understanding - as always, feel free to comment!

Laneway walk and talk

On the heels of the last research paper summary about using feeders/water/shelter to influence where your horses spend their time, I thought I'd show you our current set up.

We use a central-ish dry lot area where we have a shelter, hay and water available (and our horses go in overnight for their supplement feeds) - this concentrates their non-grazing time in the surfaced area and reduces soil compaction, as well as making things convenient for us!

Feel free to comment or question or tell me what you're doing to influence your horse's movement and standing patterns!

Research paper - Configuration of Feed, Shelter, and Water Affects Equine Grazing Distribution and Behaviors: Equine Grazing Distribution and Behaviors

This study looked how varying the position of feed, water and shelter changed how horses spend their time, and the knock on effects on their grazing behaviours.

This is important because while fresh pasture provides a number of health and mental benefits for our horses, horses can also be quite damaging to the land, quickly creating soil compaction and having a tendency to overgraze preferred plants. The authors hypothesised that horse grazing behaviour could be influenced (ultimately to protect the land) by moving their feed, water and/or shelter - this has been shown in other livestock species - so why not horses!

The research was done with six horses (small studies are typical due to costs in equine research!) in South Carolina. The horses grazed in pairs across 6 paddock sections which had three different feed/water/shelter configurations, over four time periods of seven days each (yes, I was confused too) - basically each pair of horses spent a week in each of the configurations, plus some extra randomisation to increase the statistical strength of the study. Each section was just under 1ha for the two horses, which seems a reasonable stocking rate, and half the area was rested at any one point. Clear as mud?

More importantly, what were the results?

Pasture sampling - they took grass analyses in each period, and found some minor changes in pasture that could be associated with the season (late summer through autumn), the authors did not think this was related to the experiment at hand - and I tend to agree!

-

Horse location via GPS - interestingly they did find differences in the horses locations depending on the configuration - even though the different configurations don't seem that different to me (all triangular, nothing too creative!).

Horses tended to spend more time near all three elements than not near them, with the feeder being the favourite area (14% of time), followed by the water (10.4%) and shelter (9.4%).

Configuration 2-B and Configuration 3-A (check the drawing) seemed to encourage horses to spend more time congregating around the feeder than other configurations.

Shelters were not sought out during this experiment due to mild conditions, which is a bit of flaw in the design here.

As is already well known, horses spent most of their time grazing in all scenarious (almost 77% of the time), followed by standing/resting (11%), moving around (5%) and eating their feed (3%) none of this was affected by changing the position of the feeders, waters or shelters - horses will still be horses!

So what? All in all, not a life changing study, but as there is very little data on this sort of thing in horses, it's a good start. Basically they have shown that horses will congregate around the feeder, and that moving things around won't change their basic grazing behaviours (and therefore won't have any negative impact on their health or wellbeing).

What this means in practice is that if you have an area in a paddock that has been overgrazed in the past and is struggling with compaction (or was maybe a track or similar) you can passively decrease horse traffic in that area by putting your supplementary feeding area somewhere else. To flip that scenario, you could also use this method to encourage horses to spend more time in an area that needs more grazing (longer mature grasses).

And of course what this really hammers home that if you are going to feed your horses in a set place all the time (let's face it, that's generally the most convenient thing to do!) that place will become degraded over time - so best practice would be to turn this into a dry lot area with all their feed, water and shelter in one spot to reduce the area of impact.

Perron, Brittany S., et al. "Configuration of Feed, Shelter, and Water Affects Equine Grazing Distribution and Behaviors: Equine Grazing Distribution and Behaviors." International Journal of Equine Science 2.1 (2023): 1-8.

Grass testing March 2023

It's been a minute since I sampled some pasture, but I have some new results and I am quite pleased with them!

Sugar/starch *just* sneaking in under 10% (and likely lower in the morning), energy nice and low, protein normal, good feed for our good doers to have a little graze on.

At this time last year (when it was still very, very wet) we were really surprised to see starch levels in our pastures up over 3% and up to 6%! This is really high, and not good for laminitic horses (and as this was the time when Hakon had his first episode, I suspect it was a factor). I had not seen starch this high in our grasses before (or client samples for that matter), especially over multiple months of testing.

My theory is that this has something to do with waterlogging, but I haven't been able to find an explanation yet 🧐 I'm crossing my fingers that the grass has gone back to normal and that under our good management it will maintain reasonably low sugar levels on average over the year.

.jpg)

Thanks so much for that Sophie. I can see some similarities with my set up (including size and number of paddocks).

How many horses do you have on the property?

It looks like (based off the presumed arena size), that the temporary grazing sections are typically about 20 x 40m?

How do you access the temporary sections from the semi-permanent laneway (it looks like the semi-permanent laneway is tape and treadins)?

Also, I can't see how all the temporary sections link up to the semi-permanent laneway.

We have 3, 13something hand Icelandic, 15.1h draft cross and Andalusian.

Yes I'd say roughly that size, but we vary the size depending on how much grass there is (and how fat they are!), lots of grass err on the smaller side, if we don't want to move them so soon because it's wet or we're busy etc, bit larger.

I've added some more arrows to try and explain, but possibly just more confusing! On the left side we have actually just built the laneway as we move down the sections, ending it 3 or 4 metres before the horizontal strip fence. So they enter where the red arrows are, sequentially down the paddock (it's also down hill), and the laneway gets longer to block off the previous cell.

The orange arrows show gates, so we'd leave these open for access (and the arena is fully fenced fyi, I didn't draw it in!), so to access the bottom right and middle paddocks they go through there.

And I've drawn in new green dotted lines to show how we'd adjust the grazing sections to allow access - some areas around gates will get regrazed.

Does that help??